What Is EBITDA and Why Does It Matter?

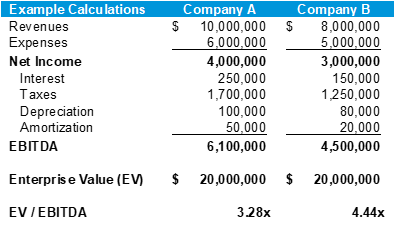

EBITDA is an acronym for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization.

It essentially serves as a proxy for the cash flow generating potential of a business. It strips out interest, which is a financing decision, because another owner of the business may or may not decide to utilize leverage. It eliminates depreciation and amortization, which are often driven by one-time capital expenditures that may be inconsistent.

The result is the amount of earnings available to pay taxes, pay for financing costs, reinvest in growing the business, and for distribution to shareholders. In this regard, it is an important metric for operational managers to understand. However, it is often cited as a metric in the valuation of companies considering raising capital or entering into a merger and acquisition (M&A) event.

The EBITDA multiple, which is the total purchase price of a company divided by its trailing EBITDA, is an often-cited valuation metric. While it is a common metric, we would like to stress that it should not be the only metric used in evaluating a company’s potential value. Like most “rules of thumb,” it is not a one-size-fits-all metric. It is a statistic.

EBITDA valuation multiples are typically unique to industries, operating trends, and specific transactions. For example, an emerging technology company may be valued at a higher EBITDA multiple than a metal fabricating business. A company with consistent earnings growth for the last several years will likely command a higher multiple than a comparable company with fluctuating earnings over the last several years. In addition, a buyer that is already in the industry may have more potential synergies that allow them to pay a higher multiple than other individual buyers could justify. Each case is unique.

Sellers may also propose “add backs” to increase their reported EBITDA, typically referred to as Adjusted EBITDA. Buyers and sellers generally review the add-backs to make sure that they are truly non-recurring, one-time events that would not be incurred in the future. Conversely, buyers and investors will also generally evaluate potential underspending or deferred expenses as adjustments as well.

Small business owners and small business brokers will often report Sellers Discretionary Earnings (SDE) or Owners Discretionary Earnings (ODE). These figures basically take compensation and personal expenses taken by the owners and add them to EBITDA. The premise is that this represents the total cash flow that another individual, acting as an active owner-operator, could take out of the business if they bought it. Essentially the buyer is buying themselves a job and will take salary plus any remaining profits. However, this metric does not apply to potential buyers that want to serve as absentee owners and hire a manager, and the parties need to evaluate potential deductions for replacement costs. Thus, valuation multiples based on SDE or ODE are generally lower than valuations driven by EBITDA.

Finally, we would note that EBITDA and SDE/ODE are not generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) figures, so readers need to pay careful attention to how the figures are calculated.

It essentially serves as a proxy for the cash flow generating potential of a business. It strips out interest, which is a financing decision, because another owner of the business may or may not decide to utilize leverage. It eliminates depreciation and amortization, which are often driven by one-time capital expenditures that may be inconsistent.

The result is the amount of earnings available to pay taxes, pay for financing costs, reinvest in growing the business, and for distribution to shareholders. In this regard, it is an important metric for operational managers to understand. However, it is often cited as a metric in the valuation of companies considering raising capital or entering into a merger and acquisition (M&A) event.

The EBITDA multiple, which is the total purchase price of a company divided by its trailing EBITDA, is an often-cited valuation metric. While it is a common metric, we would like to stress that it should not be the only metric used in evaluating a company’s potential value. Like most “rules of thumb,” it is not a one-size-fits-all metric. It is a statistic.

EBITDA valuation multiples are typically unique to industries, operating trends, and specific transactions. For example, an emerging technology company may be valued at a higher EBITDA multiple than a metal fabricating business. A company with consistent earnings growth for the last several years will likely command a higher multiple than a comparable company with fluctuating earnings over the last several years. In addition, a buyer that is already in the industry may have more potential synergies that allow them to pay a higher multiple than other individual buyers could justify. Each case is unique.

Sellers may also propose “add backs” to increase their reported EBITDA, typically referred to as Adjusted EBITDA. Buyers and sellers generally review the add-backs to make sure that they are truly non-recurring, one-time events that would not be incurred in the future. Conversely, buyers and investors will also generally evaluate potential underspending or deferred expenses as adjustments as well.

Small business owners and small business brokers will often report Sellers Discretionary Earnings (SDE) or Owners Discretionary Earnings (ODE). These figures basically take compensation and personal expenses taken by the owners and add them to EBITDA. The premise is that this represents the total cash flow that another individual, acting as an active owner-operator, could take out of the business if they bought it. Essentially the buyer is buying themselves a job and will take salary plus any remaining profits. However, this metric does not apply to potential buyers that want to serve as absentee owners and hire a manager, and the parties need to evaluate potential deductions for replacement costs. Thus, valuation multiples based on SDE or ODE are generally lower than valuations driven by EBITDA.

Finally, we would note that EBITDA and SDE/ODE are not generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) figures, so readers need to pay careful attention to how the figures are calculated.